Steelmaking Technology and a Trade Union Banner

Pride of Workplace

A trade union banner from 1920 shows latest steelmaking technology.

A set of eleven paintings of steelworks around the UK made 100 years ago shed light not only on the technology of the times, but also the working conditions and social relationships between workers. These paintings by British artist Herbert Finn were originally commissioned for a trade union banner and offer a snapshot of the UK steel industry a century ago as it emerged from the First World War. The paintings have been published as The Banner of the Steel Workers Union in celebration of a longstanding Newcomen member, Dr Jake Almond. Jonathan Aylen explains the technical background.

State of the Art in 1920

These paintings of steelmaking processes were completed on a tour of British works during 1920 by the artist Herbert J Finn (1860 – 1942). He went on to paint seven large trade union banners on silk, with vignettes of his pictures – one for each Division of the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation Union. The banner for the North West Division of the ISTC is in the collection of the People’s History Museum in Manchester, that for the North East Division in the Dorman Museum, Middlesbrough and the South Wales and Monmouthshire banner is in Newport Museum and Art Gallery, Gwent.

The paintings provide a snapshot of the iron and steel industry in Britain a century ago. They include wrought iron puddling and the production of steel by the crucible method, both then in decline. They also show the latest blast furnaces and open-hearth furnace plants together with a powerful open-die forging press. The paintings depict the arduous working conditions that existed at that time. The watercolours contain small details which might surprise.

South Wales Tinplate Works

Finn’s painting of a tinplate works not only shows technical detail, but offers a run-down of the social structure of the workforce. It also shows the working methods of the artist.

The painting shows a small tinplate works, almost certainly in South Wales, or perhaps Gloucestershire next door. The hangers for dipping packs of tinplate for cleaning in hot sulphuric acid can be seen in the tin-house to the right of the picture. The three rolling mill stands all rotate in one direction. A big flywheel is needed to maintain the momentum of a mill when a hot sheet of steel bites into the roll gap. Lydney tinplate works had a sixty-ton flywheel, for example. More stands would demand an even heavier flywheel.

As the mill rolled only in one direction, it was necessary to hand the hot rolled sheet back over the top roll before it could be sent through the rolling stand again for another pass.

The line of mills shown in Finn’s picture are steam powered via a drive shaft from a horizontal engine just out of the picture on the right – the polished steel connecting rod can just be seen. (Gas engines were sometimes used for lighter rolling duties such as the one running at Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield). Notice the spare wabbler boxes in the foreground of the painting with their cruciform openings. These mesh with the wabbler – the cross shaped end of the roll to form a simple flexible coupling between the drive shaft and the roll.

Typically, each set of mills had two stands for hot rolling as shown here – one for roughing the sheet and one for finishing. Tinplate was made from flat rectangular sheets, about three feet long, guillotined off longer sheet bars. As the individual sheets were hot rolled and got longer and thinner, they were “doubled” – folded over while hot to increase productivity in rolling – then doubled and doubled again to form a pack eight sheets thick.

Social Hierarchy of a Tinplate Mill

The centre of Finn’s picture shows the rollerman. He is receiving the hot sheet over the top of the two high mill from the catcher the other side. This looks like a long, first run “virgin” bar. The rollerman was in charge of the mill and was paid the most. His skill in judging thickness and size determined the output of the mill and the piece rates paid to his crew.

The catcher, or behinder, just visible on the opposite side of the mill was very much the junior. He had the arduous task of grasping the hot sheet with tongs as it came out of the back of the mill and swinging it over the top roll back to the rollerman. The man at the back of the picture may well be the doubler who folded and sheared the hot sheets with the help of his steel toe capped clogs. The doubler was second in command and would relieve the rollerman. The doubler worked closely with the furnace man who heated and reheated the steel sheets during the rolling process. The sheets soon cooled during rolling. All of the crew would have the support of a first helper, a time served man who would rotate through the various tasks to learn the job.

Notice the primitive manual screw down to control the roll gap. The can beside the stand no doubt contains grease for regular lubrication of the hot brass neck bearings. The hot grease would splash onto the workers. There is elementary fume extraction equipment and chimneys from two reheat furnaces at the back of the mill shed.

The rollerman wears little safety gear. He wears the customary loose, collar-less short sleeved grey flannel shirt, trousers and thick boots, but has dispensed with the customary white apron!

Women’s Work in Steel

There is a woman working here on the left of the picture, feeding sheets into the two high cold mill for polishing to improve the surface quality prior to tinning. This suggests a degree of artistic licence. The presence of a woman worker is not in doubt. Rather, cold mills for tin plate were usually separate from hot rolling. Polishing the surface required little power as there was no reduction in thickness. So a low power steam engine drive was sufficient. Perhaps the artist was keen to show every stage of the tinplate manufacturing process in one picture and has moved the cold rolling process from another bay to complete the picture. The woman or boy in the foreground of the picture with well-protected hands is an opener – responsible for separating the rolled packs back into individual sheets after hot rolling.

All this hand rolling of individual sheets began to disappear with the installation of the first continuous wide strip mill in the UK at Ebbw Vale in 1938 by Richard Thomas & Co., although it was to take two decades before the last hand mills finally closed.

For further explanation of the above tin plating process and the individual roles please see the Ashburnham Tinplate Works website. See also photographs from Trostre Cottage Museum for further images of tinplate works.

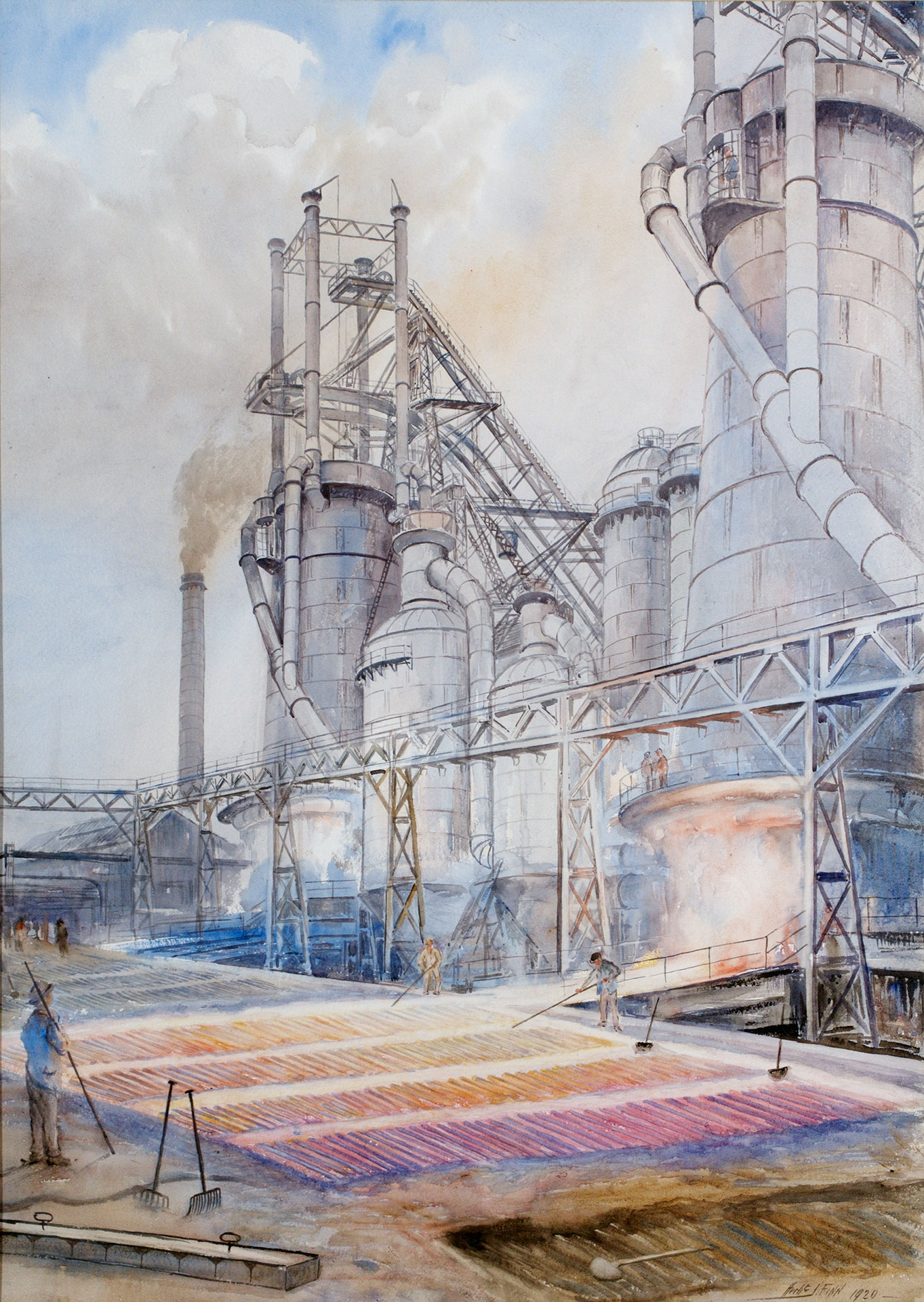

Ironworks with Two Blast Furnaces

Finn’s painting of an ironworks shows molten iron from a blast furnace being tapped into pig beds of sand to solidify. The resulting pig iron would be sold to iron foundries or to steelworks using cold charge open hearth furnaces. Both blast furnaces have mechanical charging for iron ore, coke and limestone apparently using an inclined hoist with a merry go round system of baskets. But it is not clear what sort of top is used for distributing the burden at the head of the furnace. The nearest blast furnaces has relatively modern looking single combustion chamber cowper hot blast stoves. Similar scenes can still be seen in Europe at pig iron plants such as DK Roheisen und Recycling in Duisburg, although they use a pig casting machine rather than sand beds for casting.

Crucible Steelmaking

Crucible steelmaking was prevalent around Sheffield. The picture of crucible steelmaking shows one pot of molten steel being teemed into a mould with a second lifted out of the furnace hole ready for pouring, probably into the same mould. The ceramic pots are being dried on racks above the furnaces ready to be filled with small scraps of iron and some carbon before being sealed with a lid and placed in the melting furnace below. The best known surviving site for crucible steelmaking is Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet, in Sheffield but a much larger site survives in Darnall, Sheffield which was brought back into use during the Second World War.

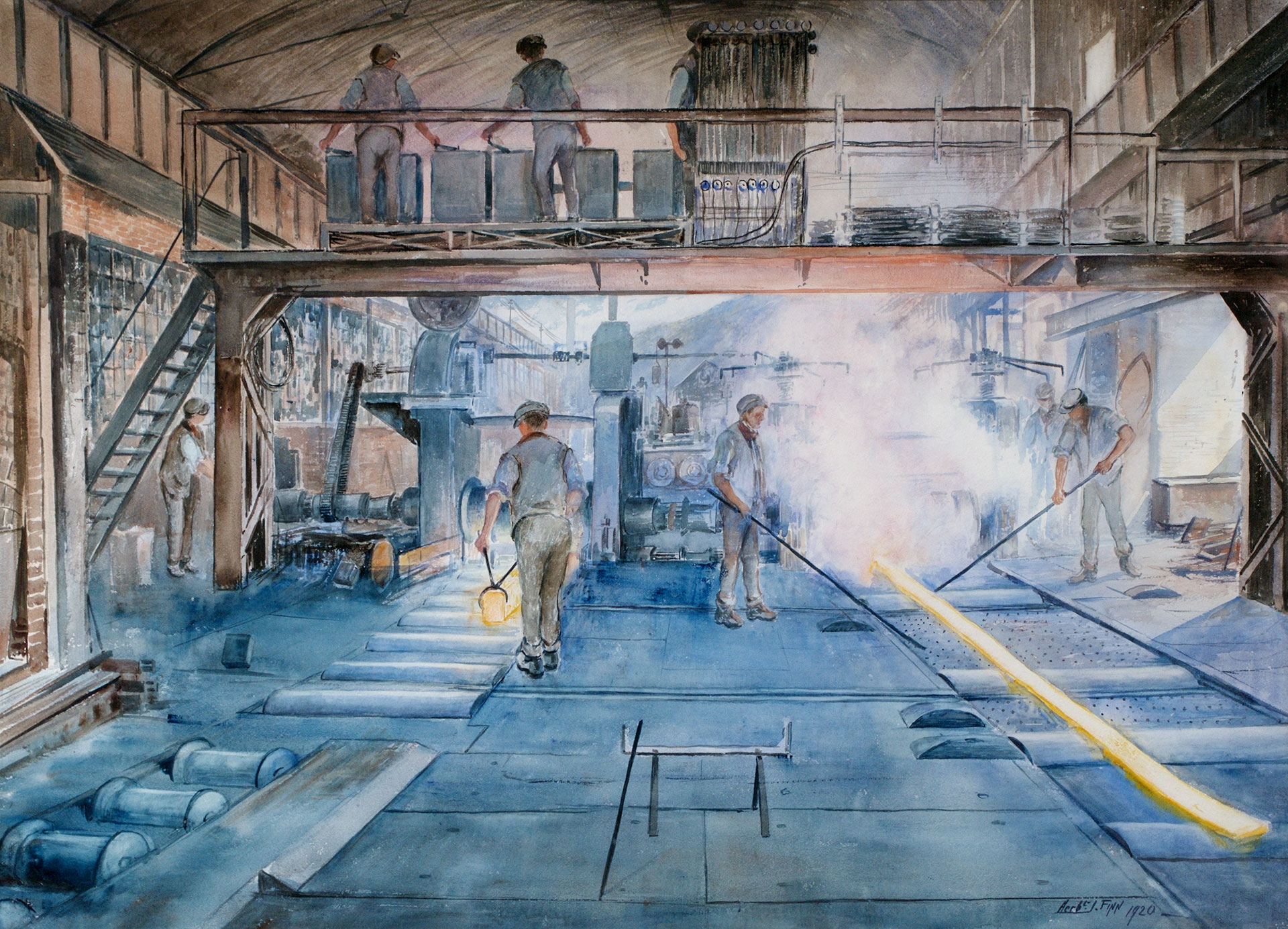

Modern Cross Country Mill

Finn’s painting of a cross country rolling mill looks conventional at first sight. But notice the electrical switchgear on the platform above the mill. The rollermen on the platform are regulating the speed of the two mill stands and reversing the flow of material on the roller tables and through the mill using electrical controls. This is a pioneer electrically driven mill in 1920. Frustratingly, we see nothing of the electric motor or the incoming power supply. Nor has it been possible to identify this particular mill. There is a chain driven screw down on the billet mill to the left. The rollermen standing on the run-out tables are there to turn and guide the hot material through the next pass line.

Tribute to Jake Almond

The Cleveland Industrial Archaeology Society became involved in the project to publish the paintings of Herbert Finn as a result of Jake Almond’s interest in the paintings when they were exhibited at the Kirkleatham Museum in 2007. Jake was a long-standing member of the Newcomen Society and a stalwart of the Cleveland Industrial Archaeology Society. Jake made arrangements to have Finn’s water colours professionally photographed. Following Jake’s death in 2018, the book was an appropriate way to acknowledge his massive contribution to Industrial Archaeology on Teesside and as a reminder, lest we forget, of the contribution that the workers in the iron and steel industry made to its success, often at risk of their lives.

The Banner of the Steel Workers Union

The original water colour paintings were photographed whilst on display at Kirkleatham Museum in 2007, where they had been loaned by the trades union ‘Community’– the new name for the ISTC.

The book The Banner of the Steel Workers Union is 29cm x 21cm, 32 pages with 11 colour plates of the paintings and includes a memorial to Jake Almond with a list of his publications and a brief history of the artist. A limited number of copies of the book are available from:

The Hon Sec

Cleveland Industrial Archaeology Society

24 Albert Road, Fairfield

Stockton on Tees TS19 7EW

Price £10.00 including postage within the UK.

The CIAS acknowledge the support of the Community Union in allowing these watercolours to be photographed. The author Jonathan Aylen is responsible for the commentary here.

Are you a member of the Newcomen Society?

Having just celebrated its Centenary Year, the society has published over a 1000 papers in The Journal – an invaluable archive of original research material published twice a year, covering all aspects of engineering from ancient times to the present, plus available to browse and download in our FREE TO MEMBERS Archive.

Full Membership includes:

- Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology (two issues, one volume per year)

- Printed and/or PDF versions of LINKS, Newcomens’ newsletter (published 4 times a year)

- Free access and download facilities to the Society’s Archive of past papers back to 1920 (The Journal)

- Membership of local branches and subject groups

- Access to the website’s Member Area offering access to research sources & access to other members (subject to privacy permissions)

- Attendance at summer meetings, conferences, lectures and study days.

Query Re the illustration of the blast furnaces with mechanical charging on the Banner of the Steel Workers Union. There was a system like this on a single blast furnace constructed by Head Wrightson at the Clarence Works of Dorman Long & Co Ltd, Middlesbrough. It is believed that a similar system was used in South Wales. Can anyone identify the system and/or the blast furnaces it was used on?

The rather older blast furnaces on the South Durham site at South Bank, on the immediate outskirts of Middlesbrough, had the four column arrangement shown in the painting. ( That is older than the ones at Clay Lane at Dorman Long, the first of which were commissioned around 1957.)

Looking at the picture, the valving arrangement at the tops seem to suggest that they are vent pipes for releasing pressure in the blast furnace or, more likely, to disperse blast furnace gas during charging.

Thanks for including this set…..it takes me back to a branch of Dorman Long about half a mile down from the Newport Bridge, where there was an ancient steel rolling mill producing “sections” which were not much more than a few inches across. It was similar, but perhaps a bit smaller than that shown in the painting of the “Modern Cross Country Mill”

All the handling was done by men, and the conditions were appalling. Everything was much blacker than what was shown in the painting. The mill must have been part of the ironworks at Newport on the River Tees. When I was there in the early sixties, one could see the remains of the blast furnaces, as rings of barely visible brickwork next to a rough path leading from Dorman’s research centre to some buildings where we were attempting to plastic coat steel angle sections.

There are no notes about the wrought iron puddling furnace. This might be of interest.

Puddling was a method of removing carbon, silicon and phosphorous from pig iron, which on completion produced wrought iron, a material with similar properties to “steel” as most of us know it. That is, like “mild steel”, wrought iron had high ductility, could be bent at room and high temperature, and had more than enough strength to be used in applications where high tensile strength was needed. Up to late Victorian times, it was rolled down to make railway lines, girders and plates, and forged to make the connecting rods and crankshafts of steam engines.

But, as the painting indicates, puddling was a slow and manpower intensive technique, and with the coming of the manufacture of mild steel, using the Bessemer and Open Hearth processes, wrought iron began to disappear. There would have been very few outfits making wrought iron in the 1920s. On Teesside, puddling using the high phosphorous pig irons, made from the ores of the Cleveland Hills may have had special value when the Basic Bessemer process was in use……The slag from the puddling furnace could be treated in such a way that it could be added to the charge of a blast furnace.

What we are seeing is the final stage in the puddling process. The bulks of pig iron that have been melted down in the furnace have been partially oxidised, turning the carbon into carbon monoxide and the silicon into an iron silicate slag, but leaving an almost pure iron behind. The procedure raises the melting point of the mass in the puddling furnace from around 1150° to well over 1500°C (adding impurities to a pure element almost invariably reduces the melting temperature). As the furnace cannot attain the melting point of pure iron, the puddled iron consists of a semi-solid mass. In consistency, it would be like globs of plasticine stuck together with honey. The plasticine being the iron, very soft at such a high temperature, and the honey, the semi molten, iron silicate slag.

In this form the puddled iron is cut up, while in the furnace, into irregularly shaped balls which are dragged out of the furnace onto the small cart, as shown in the picture. Each ball is then wheeled off to a forging hammer where the bulk of the slag is squeezed out. As the artist has tried to show, the “ball” is incandescent.

My late great uncle was presented with a print of these paintings by BISAKTA when he left the Bryngwyn Steel works in 1927 and I’ve been trying to find out more about it and the artist so this is very interesting to read. His print contains all 11 pictures. The print now hangs in the Canolfan Gorseinon, a community centre built on the site of the steelworks.